Living with Dogs and Photographing them

Essay I wrote for a class. but also I just want to document my life with my companion-species

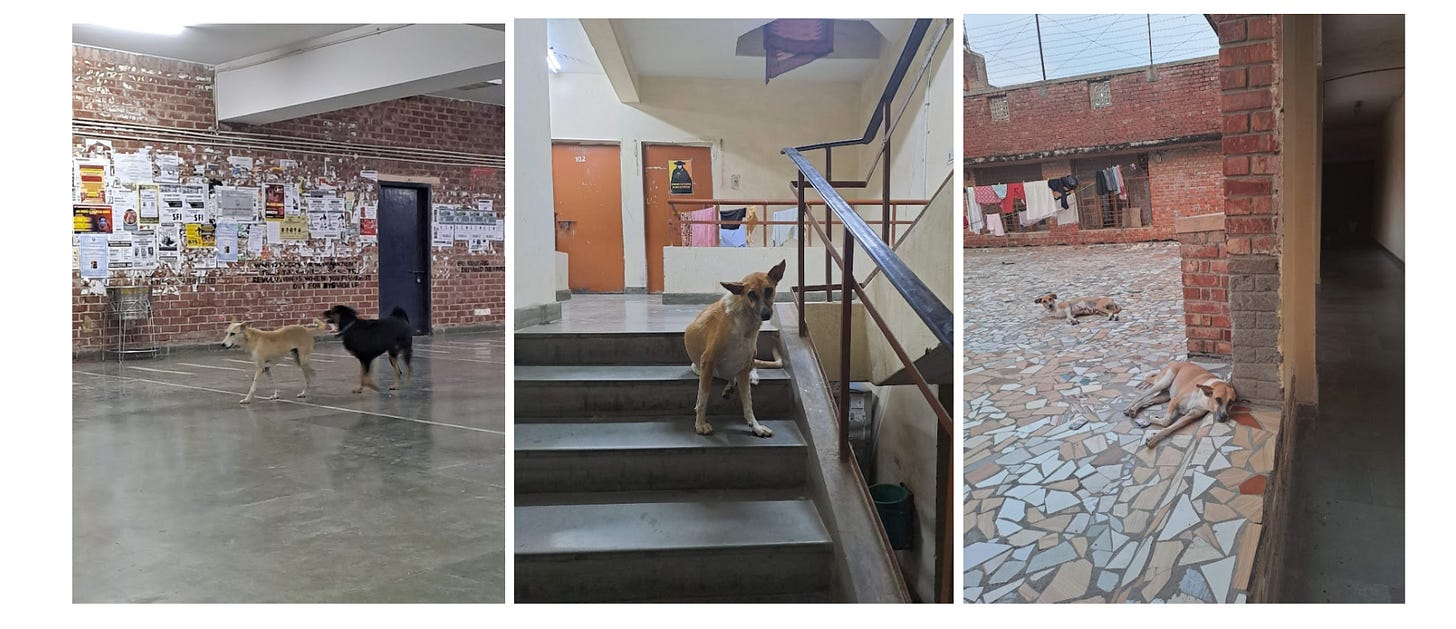

I have been documenting my encounters with the dogs on campus in the form of a photographic archive within my phone — in my hostel, on the side of the road, outside the department buildings and near the various Dhabas and eating points. The Society of American Archivists defines a photographic archive as “A collection of photographs, often with accompanying materials in other formats, made or received by an individual, family, or organization in the conduct of affairs and preserved because of the enduring value of the information contained in those records (SAA Dictionary)”. What information am I seeking to record here? What is the purpose of my image archive? Is it just my tendency to be nostalgic and my sentimentality? If that is so, is Affect not enough?

I have been thinking about what my archive means in a scholarly sense, and how my photographing of these stray dogs differs from taking photographs of my pet dog in my home. The dogs on campus (Bingo aside) do not depend on me for food, shelter, or any of their other survival needs. In some ways, the stray dog is an entity of its own — they are free to roam, more independent, and therefore more dangerous, more uncertain, and more of a risk than a collared pet dog living inside the safe premises of a household. A stray dog is riddled with disease and answers to nobody. I looked around the internet for stray dog photography and I stumbled upon this Daido Moriyama image from 1971, titled Stray Dog. It features this menacing-looking dog who seems to be baring its teeth at us, looking back at the viewer almost ready to pounce at any given moment. I have not met this dog and cannot attest to its nature, but the image represents the eternal potential threat of the stray dog as an unknown creature. Dogs are domesticated animals but stray dogs are feral and untamed and are still seen as more primitive and closer to nature than house dogs, which are docile and within human control. Our relationship to stray dogs as photographic subjects is mired in a history of whether we possess control over the animal or not. Purebreed dogs are considered safer to human beings, because they have historically been subject to more human intervention. The stray dog is a mutt, a mixed-breed entity and represents a kind of uncertainty that humans cannot deal with, and maybe we harbour a resentment towards them for it?

The central theme of this essay is perhaps — What does it mean to work with dogs as the subject of your photographs? I have been told ever since I was young not to pet stray dogs because their behaviour is unpredictable and they can bite me at any moment but pet dogs (purebreds more so than others) are alright because they are safer, always vaccinated, and will never turn on me. Granted, this depends on the breed and size of the dog but I can confidently say that this is true for most cases. The dogs in JNU are not quite completely strays, as they are cared for by several of the Pet NGOs on campus, but they are strays in the sense that they wander freely, and have no defined “owner” or “family”. I feed a lot of these dogs, and I am extremely familiar with the ones inside my hostel, so I have a relationship with them. The people in the Paws Foundation have also named these dogs, and naming an animal establishes a kinship bond that takes them out of the stray space and brings them closer to “pet” territory as it implies some level of anthropomorphizing of the animal, and assignment of some unique attributes that make the animal its own individual. Anne Carson, in her poem, Between Us And, comments on how we humans name dogs:

“and when

choosing to name

individual animals we

pretend they are objects

(Spot) or virtues (Beauty)

or just other selves (Bob).”

Dogs are named after some particular trait they may embody, sometimes physical, it is something that is obviously visible to us, or it may be a personality type we have thrust upon the dog. Or they are named the few common dog names along the lines of Jimmy, Bruno or Brownie, or Tommy. In India, we encounter all these names and the occasional Bhairava or Raja too.

Some of the photographs I have taken of these dog-subjects have required me to go quite close to them and earn their trust enough to bring the foreign object of the camera close to their faces. I believe this trust has been earned by continuously calling them by their names, talking to them, petting them, and feeding them.

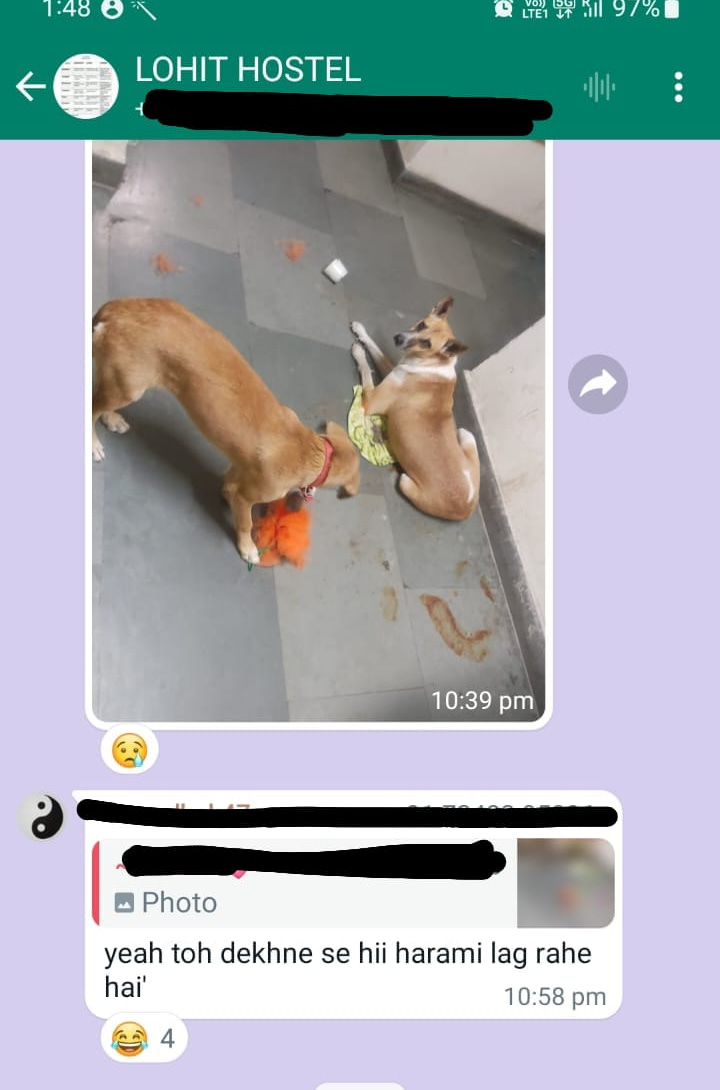

I have observed animal photography to be similar to the way in which children are captured. Dogs too, like children, have no agency in the representation in the photograph, and they are often anthropomorphised (text is added to the image to make them say something, they are dressed up in human clothes etc) and there is great emphasis on getting the dog to “pose” for the photograph. For every clear photograph of a dog I have, there are maybe ten blurry photos of them moving non-stop where one can hardly make out that there is an animal in the frame, let alone a dog. It is different from a human being posing because a human being knows what a photograph is and the non-human subject does not. Stray dogs images are produced for a few broad purposes that I have identified as: for leisure, for medical purposes by vets, for spaying/neutering purposes by the State, for fund appeals or adoption appeals by animal welfare organizations, and by complaining civilians who have seen these dogs create some disturbance around them and want them to be removed from their surroundings. Every month at the General Body Meeting in Lohit Hostel where I live, some people demand that the dogs should not be allowed in the hostel premises and relegated to the outside area because they are inconvenienced by the havoc they create. They post pictures of the dog culprits themselves, or the mess that they create on Whatsapp groups to alert the other residents of the dog’s antics. Thinking about Dogs and the waste they produce also asks the question of “Who is responsible for dealing with the bodily waste of stray dogs?”

A photograph of a stray dog is never just a photograph of the dog itself. Every stray inhabits the road, or the footpath, or the corridor, or the staircase, or a specific open area of this sort. Images of stray dogs are also images of the roads they occupy, of the people in the backgrounds, of the crimes that happen on the road, of the eateries they get their sustenance from, of the garbage they rummage through for their meals, and of the trees and rocks and natural landscapes of the urban areas they live in. The stray dog is who I would call the ultimate flaneur — these dogs know the campus and the city’s victories and failings better than I will ever dream of knowing. I searched for photography collections of dogs in cities to no avail, but I did find an image collection of cats on the streets of Tokyo taken by Nobuyoshi Araki in 1990. If there is anything the literature on the history of photography has taught me, it is that there is great value in finding out what is hidden and obscured within the frame of the photograph. There is much to be gleaned about Tokyo in the 1990s from this collection of images. The cats are urban subjects, citizens, going about their lives. They are not posed and the photograph is not constructed in any way. It is a photograph of Tokyo and the cat happens to be there. The cat constitutes a non-human, natural but still urban subject living in Tokyo and is a binary opposition to the human, cultural, and city dwellers of Tokyo who are also walking to the nearby shops, perhaps. The cat is occupying the same space as them, crossing the road and resting under the motorcycle.

Berger, in his essay Why Look at Animals? says that animals are always observed (Berger 14). The pet is a household member and is always surveilled similar to how the dependents and minors of the house are. Wildlife photography has made it so that animals are constantly accessible to us through wildlife channels, magazines, and documentaries through the lens of the night vision camera, the invisible camera and special photography equipment designed to be discreet so as to not spook the animal away. Stray dogs are constantly surveilled in order to watch out for the smallest transgression - be it a bite, entering a private space, or or any noticeable symptom of disease. He says that while we are continuously observing them, the fact that they watch us too has lost all meaning. So are the dogs watching us too? What would they say if they could photograph us? As we gain more knowledge about them, it only reaffirms our humanness contra their animality (Berger 14). We have language, and our dogs do not, which makes it almost impossible to understand their beliefs and desires.

What does it mean to photograph our animal subjects, without anthropomorphizing them in the process, and take photographs of them as they are? I want to first establish the caveat that anthropomorphizing our animals is not a crime, as it is spoken about in socio-ecological circles. In my reading of Haraway’s Companion Species Manifesto, I found her seminal distinction between “thinking with”, and “Living with” to be quite useful to my quest. She says that dogs are not a “surrogate for theory” but complex species that we live with, whose history is joined with human history. Photographing these dogs, for me is a way for me to inhabit the life of this dog with whom I am living on the same campus. The dog is not able to tell me things, but I am trying to glean from my photographs of them how they live, what their daily routines and habits are, what they eat and eventually what they must be feeling. I am engaged in this life-long journey of pursuing the inner life of the “intimate other”. I am bound to screw up, get bitten, fall in love, be rejected by the dog-subject at different points in this endeavour. Once the act of photography is over, I look at the photographs and also circulate them on my social media and among all my friends. Reflecting on these campus dog photographs produces different affects in me depending on the type of photograph and my relationship with each of the dogs. And in this process of reflection, I am making comments about their poses, about their expressions, and their locations, all of which carry a great deal of anthropomorphism. The way Haraway conceptualizes human-dog relationships without demonizing anthropomorphism is central to my photographic practice. All of her writing, not limited to the Companion Species Manifesto alone, is about recognizing our species difference and continuing to work with that difference with the commitment to building a radical future in these precarious times (See also, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene). I am photographing these dogs to remember the ecosystem of this campus. I have lived with these animals, and that relationship is one that needed memorializing for me. I know that the larger dilemmas of whether we can ever correctly represent the dog-on-JNU campus experience with their agency and subjectivity are not answered through my photographs or this essay. But it is still interesting and a worthwhile enterprise for me to build this archive of these dogs and continue to live with them as companion species. The stray dog is an elusive photographic subject and an unwanted entity whose images are shared around the world and most people photographing these dogs have little to no relationship with these dogs, beyond them being a vessel for the city or geography they are documenting, and then when they do have a relationship with the dog, it is fleeting and lasts only for the photographic moment and a few minutes prior to and after it.

The logical next question to ponder over with photography is the one of circulation that comes after the photographing act - What happens to these dogs once they are suspended within the photograph inside my phone? What is one to make of the digital life of these images? My friend keeps reminding me that the digital is a world that makes nostalgia all too accessible because we have little reason to conjure up images in our minds when they are readily accessible to us. I’ve got these dog photos on my phone and I look at them every now and again in fondness, in sadness, longing or sometimes just to show somebody something funny the dog did in the photo. For me, the photography is an act of kinship. My understanding of the photograph is that it is a dynamic, moving, polysemous thing that can evoke a great deal of these affects and sentimentalities in me. All affect emerges in the relations between two entities, the photograph and me. The dog photograph archive is also doing something to me. WJT Mitchell in his book What Do Pictures Want? writes about conceiving photographs to be "animated" beings, quasi-agents, mock persons” with desires, and intentions and that cannot be reduced to the language of interpretation, or language itself (Mitchell 47). And I’m using this as an anchor to think about what my dog photo archive wants and I don’t have a definitive answer yet.

Works Cited:

The companion species manifesto: dogs, people, and significant otherness. By Donna Haraway. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press 2003

A Photographic Archive. Society of American Archivists Dictionary

Daido Moriyama, Stray Dog. MoMA 1971.

Berger, John “Why Look at Animals?” About Looking Pantheon Press, 1980. Pages 1-26

Nobuyoshi Araki, Living Cats in Tokyo.

https://japaneseavantgardebooks.com/products/living-cats-in-tokyo

6. W. J. T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images Chicago, 2005.

Loved reading this